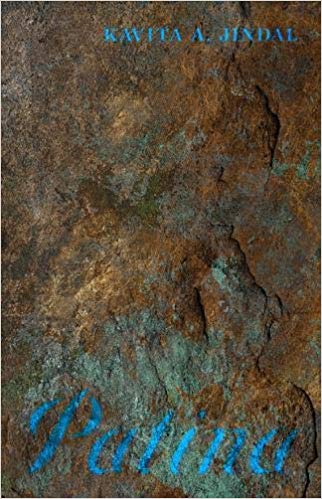

Poetry cluttered with lists or images dressed in poetic descriptions pretending to create a lyrical experience to revel in are quite common. It is also, largely celebrated by magazine editors and flourishing winning awards. So, I was not surprised to read in the June/July issue of The London Magazine, Paul Griffin’s essay ‘How Not to Write Poetry’, discussing how the teaching of poetry is left quite wanting. He laments that in this learning process students make ‘lists of words and then write poems using these words describing objects or situations.’ Recently, there has been a wider debate about ambiguity in poetry as well. Griffin also makes a point that ‘poems are very often little more than a jumble of disconnected images.’ The nature of the ‘spoken word’ culture that now engulfs us bears no compass to what real poetry recital should be. Additionally, we must remember that just the traditional construction of poetry with rhymes and metres does not always make poetry. It must deliver us to the challenging content. Hence, when I apply the mentioned canon to three recent collections here, I put them in this order: Patina by Kavita A Jindal, then Tigress by Jessica Mookherjee and finally, The Waiting by Usha Akella. I rush to point out, however, that each poet’s approach is completely different in lyricism, in applying traditional forms, and in making poems transcend from ‘describing objects and situation’. With magical simplicity, Jindal connects easily with readers by steering away from describing objects or situations. Mookherjee’s world is quite leaden with descriptions, and Usha Akella, suitably for her devotional quest, completely sheds worldly clutters and detailed events.

Jindal’s softer and measured but reflective voice serves her well in achieving a startling realism, often magical. Her scattered observations are well weighed up to create a mood wrapped in an endearingly lyrical language. She has poignancy and grace laced in simplicity. In ‘Anything But’ this example of simplicity speaks volume where—‘On Not Being a Muse’—a woman is objectified by an artist (man?) and has to deliver a portrayal, but in conclusion will not be ‘static’, call it her liberation from the expected perception.

Gladly I will do it all Anything but be

Static while you are active Anything but be

The one from whom you source

What you make your own.

Jindal’s poems show us that the beauty around us is not the derivative of any ostentatious aesthetics but the metaphorical patina. Patina brings time, history and value into play. This metaphorical patina assimilates from one’s reactions to adverse encounters in life. Her poem ‘Piccadilly Line Salon’ brings this point home by the poet putting us in the middle of women peering, pouting, slicking, and flicking doing their make-up in the morning on the tube. It contrasts with ‘Should I rustle in my satchel? / Check in a mirror/ for bits of breakfast pear/ stuck in my teeth?’ We are left wondering about the artificial images wearing the make-up versus charming and unassuming reality; the pitch is of the artificial against the natural. Jindal succeeds in her craft with lyricism and restrains as displayed in her other poems about the lack of clean water for some, Brexit, hashtag, Trump, and Boris. Thus, while the poet engages with personal perspectives, she also indulges in current affair concerns. Here is a poet that claims ‘When slow living comes back in fashion/ I will claim as I have always done/ …That I was here first.’