In his new book, Jairam Ramesh transports us to a time of remarkable consequence for India today. While the author inserts a caveat that the book must be read as a biography of a committed and profoundly sagacious bureaucrat, the running commentary on the times that produced this man can hardly be ignored. This is a man who spoke of secularism as a civic, worldly matter and distanced the idea from its present connotation as an anti-religious doctrine. This is a man who doggedly harped on the role of science in a modern state and fashioned some of India’s best institutions committed to discovering the new. But the book is also a foreboding, captured best in a typical Henry Kissinger quip, ‘…Not that a strong India will be any joy to deal with.’ (p. 147)

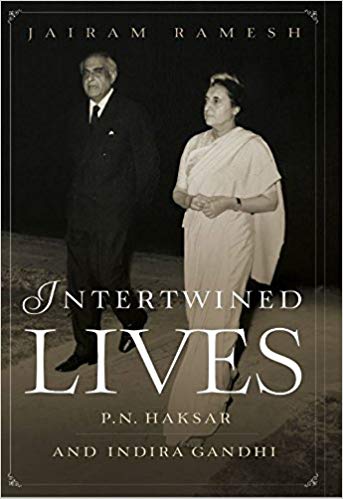

Ramesh’s biography is better characterized as a political biography. There is no disputing that. From the very title of the book, Intertwined Lives, it is easy to see that the book is preoccupied with using Haksar as an alibi for the times when Indira Gandhi was a towering figure in Indian politics. To be sure, an alibi for the times, not Indira Gandhi herself. Of course, the charge of an alibi is a provocative one but it is to merely reflect upon the ebbs and flows of Haksar’s public career—and the culture of service that he represented—corresponding closely to ‘Good Indira’ and ‘Bad Indira’. Ramesh dispenses with the early life of Haksar with pithy comments and reserves, for anyone interested, the information that Haksar did write a memoir on his early life. Meat is added to the bare bones of Haksar’s life from his time in England as a young student and the wide network of friends and ideological influences that he imbibed. Haksar, in Ramesh’s telling, remained loyal to both his friends and the ideological influences of those days. The man who returned from London was few shades pinker than some of his more illustrious ‘red’ friends of the time. Haksar briefly spent time with the then undivided Communist Party of India (CPI) in Nagpur but was soon to be subsumed within the nascent bureaucracy of post-Independent India under Nehru. And this is where the chapters begin to grow voluminous.