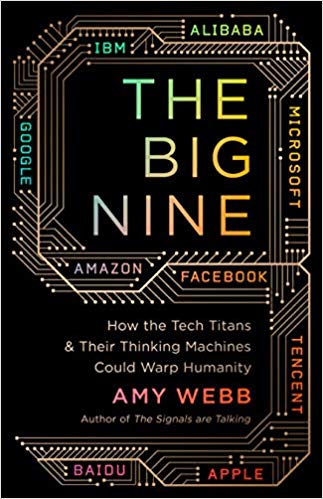

In an eye-opening and timely analysis of the world’s two divergent technological paths, the renowned futurist Amy Webb in The Big Nine: How the Tech Titans & Their Thinking Machines Could Warp Humanity charts out the potential scenarios for an Artificial Intelligence future, pitting the United States and China in direct opposition to each other. Her balanced critique of nine major technology companies of the world—Google, Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Tencent, Baidu, and Alibaba—presents a cautionary tale to champion an ethical blueprint for AI development.

Early on, the book’s most gripping analogy circles around AI’s mastery over professional Go player, Fan Hui. After three rounds of playing the centuries-old Chinese game Go with a computer, ‘[r]eeling from frustration, Hui had to excuse himself for a walk outside so that he could regain his composure and finish the match. Yet again, stress had gotten the better of a great human thinker—while AI was unencumbered to ruthlessly pursue its goal. That brings us to a perplexing new philosophical question for our modern era of AI. In order for AI systems to win—to accomplish the goals we’ve created for them—do humans have to lose in ways that are both trivial and profound?’

Webb’s three-pronged layout of an optimistic, a pragmatic, and a catastrophic potential future gives us three probable paths to answer this question of human-limiting AI. In doing so, she successfully problematizes the small group of people who have amassed disproportionate decision-making power in the process (the AI’s tribe of the Big Nine technology companies) and shows their two global faces—American and Chinese.