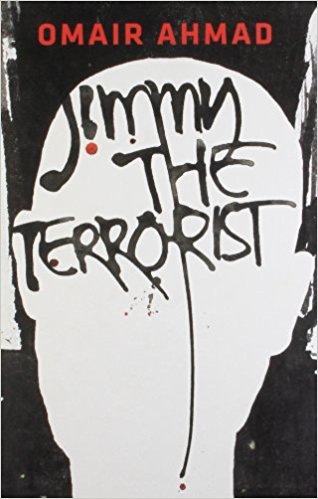

Ashish Khetan’s cover story, ‘Dazed & Confused Again’ (Tehelka, Vol.8, Issue 37, 17 Sept, 2011) traces the growth of one Abu Faizal Khan, an IM operative from Hansapur village in Azamgarh, UP. The tenor of Khetan’s report is no different from the reality of Jamal Ansari, Omair Ahmad’s protagonist in Jimmy The Terrorist. Both echo Jawaharlal Nehru’s prescient concern, voiced in a letter to the Chief Ministers of Indian Provinces in 1947, ‘We have a Muslim minority… . We must give them security and the rights of citizens in a democratic state. If we fail to do so, we shall have a festering sore that will eventually poison the whole body politic and probably destroy it.’ (Letters to Chief Ministers, 1947-1964, Edited by G.Parthasarathi). The relevance of Ahmad’s story in the present context is most certainly not lost on the reader. In fact, perhaps it is more relevant today than when it was first penned as a short-story, in the context of the riots following the demolition of the Babri Masjid.

The ‘Prologue’ fluidly unravels the unity of time to gird and develop the unity of space, Moazzamabad, more specifically Rasoolpur. From a Peepli-esque scenario of journalists ‘descending like kites upon a fresh kill’, Ahmad effortlessly weaves in large swathes of time, from the coming of Aurangzeb’s son Moazzam Shah, through the 1857 revolts to the demolition of the mosque in Ayodhya. The arborescent growth of the Hanuman temple; the casual stop-over of Qazi Mohammed Murtaza Rasool, who lends his name to the mohalla that is recorded in no government records; the clearing of jungles for settlements signifying a hot-pot of merging religious identities (Jungle Subhaan Ali, Jungle Vishnu Das and Jungle Mosley Sahib); the cultural mooring that Shabbir Manzil provided to the impoverished mohalla; all these become the minutiae of the colourful weft that is woven over the warp of the quotidian lives of the people who lived with their ‘everyday prayers and fears, their suffering and resilience’.