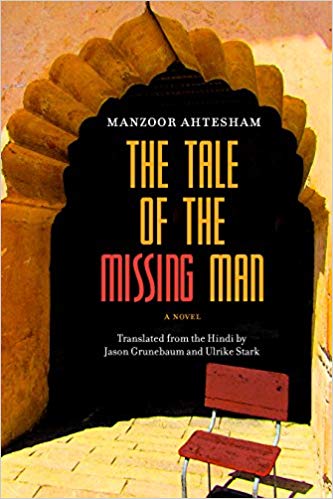

The Tale of the Missing Man, the newly published translation of Manzoor Ahtesham’s Dastan e lapata is strikingly prescient. Originally published in Hindi in 1995, Ulrike Stark and Jason Grunebaum’s translation brings Ahtesham’s masterpiece to an English reading audience at a time when the relations between the Indian state and Muslims are once again at the heart of the political debate. The Tale of the Missing Man can be read as a postmodern inquiry into ideas of the self, and the position of Muslims in India around the time of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement and the Babri Masjid demolition.

The novel is structured around the protagonist Zamir Ahmed Khan and his internal and external struggles as he tries to make sense of the fast-changing world around him. Zamir suffers from a mysterious disease which slowly but surely limits his ability to move freely around his hometown of Bhopal and causes him to spend most of his time alone reminiscing about his life trying to understand where it went wrong. The tongue in cheek tone of the novel mixes descriptions of genuine struggle with questions regarding the separation between the author and his protagonist, and between truth and fiction. The Tale of the Missing Man manages to be both challengingly playful, stretching the boundaries of the pact between the author and the reader, while touching painful questions regarding an individual who is unable to integrate into his surroundings.

Muslim authors writing in Hindi such as Ahtesham are often read through the lens of their religious identity rather than through the texts they write and they anticipate this in their writing style and tone. Muslims writing in Hindi occupy a special position as they confront the automatic association of Hindi with Hindu. These authors challenge assumptions about the division between Hindi and Urdu and deny the possibility of delineating clear borders between Hindu and Muslim experience. Ahtesham plays with these expectations and blends the two languages in such a way that their separateness is questioned. Possibly, translation cannot express this aspect, but the supple English used in this translation succeeds in transmitting the ironic edge and humour of Ahtesham’s language.