and when we speak we are afraid

our words will not be heard

nor welcomed

but when we are silent

we are still afraid

So it is better to speak

remembering

we were never meant to survive

–Lorde 1978, lines 37-44

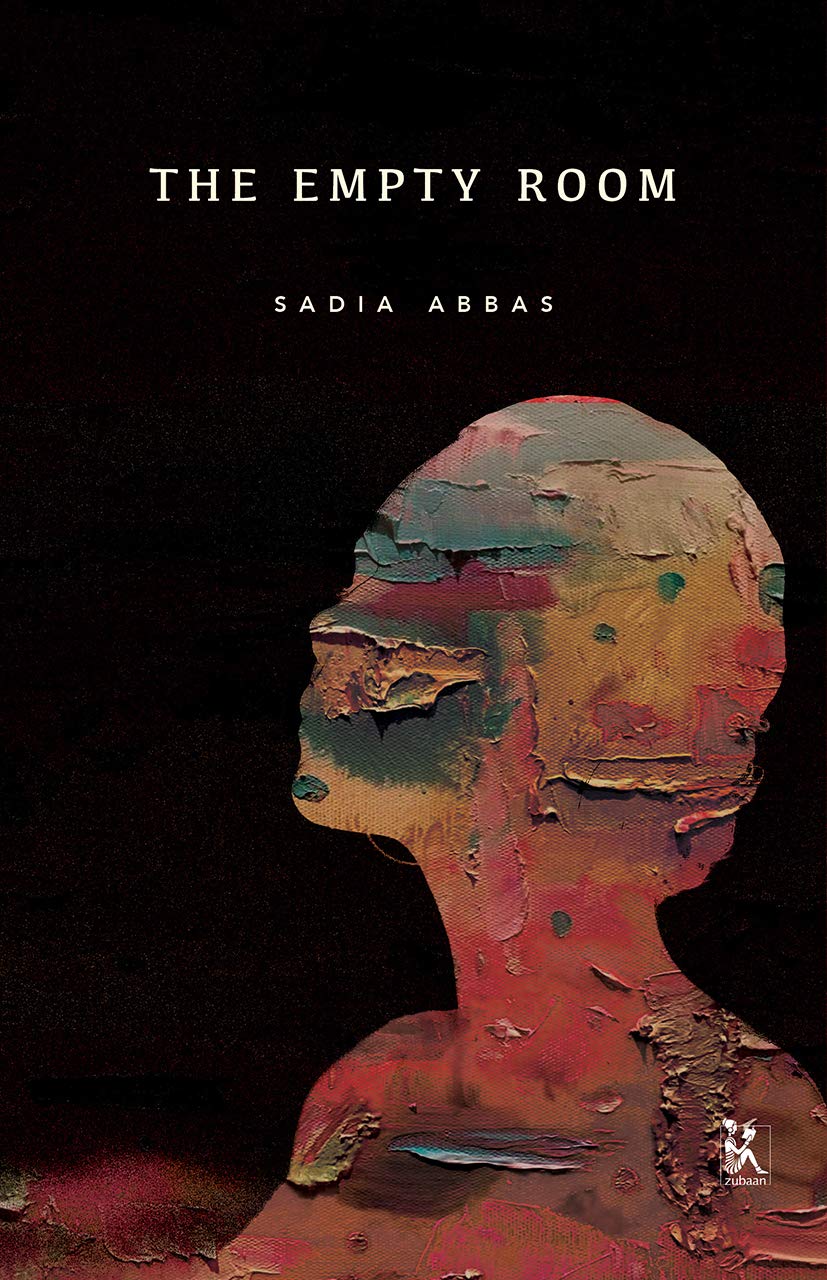

Sadia Abbas’s debut novel, The Empty Room, is a diligently crafted piece of work that details the intricacies of the life of a married woman in Pakistan. The character-driven story unfolds in Karachi between the years 1969 and 1979, a period of immense political tension in the country, and in the author’s own words, ‘one of the most turbulent times that the country witnessed.’ Four regimes came into power during this tumultuous time and the country was steeped in civil war. The personal often crisscrosses the political, and while critiquing gender norms, the novel also evaluates the political state of the country.

Much has been said and written about the proliferation of Indian fiction in English. But academic literature, on its Pakistani counterpart, is relatively new and it is an area that has immense potential for further research. However, it can be said that there has been a recent development of Pakistani fiction in English, especially post 1990s. Like India’s Midnight’s Children moment, this fiction was put on the international map by a series of novelists which included Kamila Shamsie and Mohsin Hamid, among many others. In The Empty Room, it is evident that Abbas has been influenced by the themes that Kamila Shamsie deals with—the political and the personal. Indeed, much like Shamsie and most other Pakistani English novelists, Abbas is settled in the West but seeks to become an authentic voice of the nation and the many struggles it went through.

The protagonist here is Tahira, a talented artist who is married off to Shehzad, a wealthy young man. Her monologues hint at a progressive upbringing, and she surrounds herself with friends who are politically active with a modern outlook. Her brother Waseem is a socialist and her best friend Andaleep, like Tahira, is a staunch feminist. But her marriage proves to be less than successful. The novel foregrounds the unequal relationship between the two families (Shehzad’s and Tahira’s) at the very onset, and the author does this without any theatricality. The readers are familiarized with this equation in a no-nonsense and matter-of-fact manner. Take, for example, the way in which the novel opens. It is Tahira’s first morning waking up in a different house, next to her husband. To her humiliation, her sisters-in-law barge into her bedroom and ask her to get out. And as soon she comes down, she is chastized by her mother-in-law about the inadequacy of her dowry and the cheapness of her belongings. As Tahira learns soon, everything about her marriage is a facade, a show to keep up appearances.