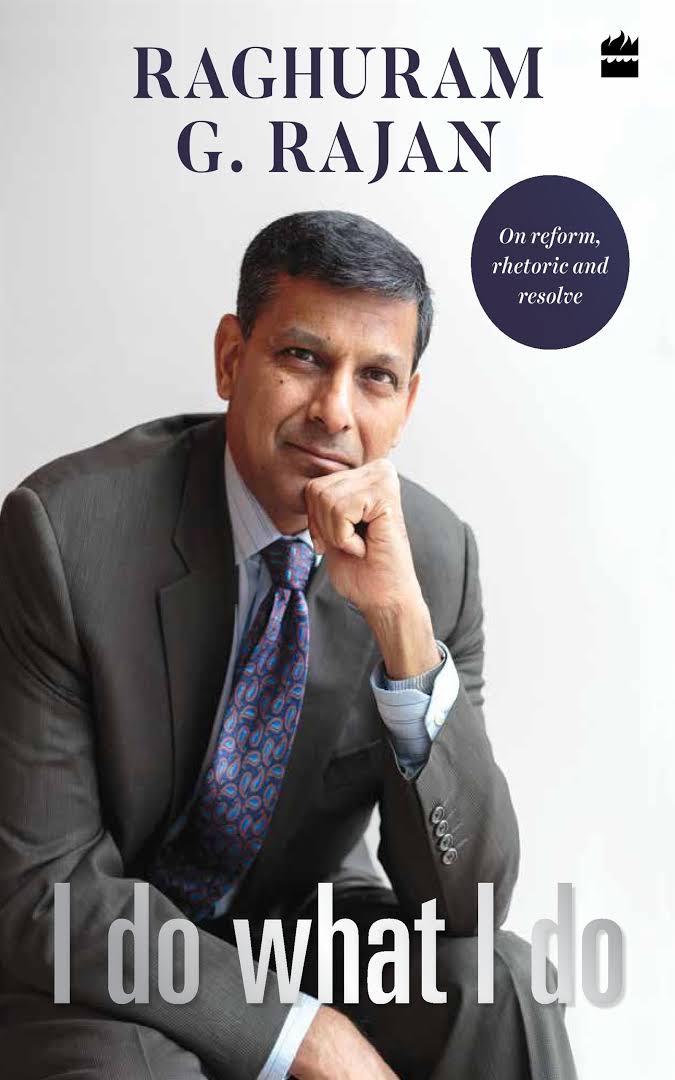

Raghuram Rajan, the erstwhile ‘Rockstar’ Governor of the Reserve Bank of India, came to India with an awesome reputation. He was a Professor of Finance at the prestigious Chicago University, had served as Chief Economist in the IMF, and had written widely acclaimed books on the western financial system. Above all, at a time the US ‘Goldilocks’ economy was chugging along merrily as if there was no morrow, with economic growth and asset prices at an all-time high, a strong dollar despite growing current account imbalances, and low and stable consumer price inflation despite seemingly growing above potential, he was one of the few economists to presciently draw attention to the dangers implicit in the US financial system. This was as early as 2005 in his now celebrated paper presented at the annual Jackson Hole gathering of central bankers from around the world.

December 2017, volume 41, No 12